In one of his countless interviews Friedrich Gulda remarked that those who cross boundaries are considered by society either as “revolutionaries or fools.” That, like so many of Gulda’s views, is somewhat exaggerated and simplistic, but there lies a kernel of truth in this assessment: going beyond the boundaries of our ordered world, one can either discover a land of wonderful possibilities or shipwreck in a stormy sea losing orientation and direction.

Crossing boundaries in music can mean many things. There is the crossing of genres, often between musics of various regions, times, or social niches. Then there is the crossing of the boundary between what is considered to be acceptable as music (the norm) and what is considered non-music (avantgarde). Finally there is the crossing over of the musical work into a musical space in which the performers and listeners are not constrained by Werktreue or composers’ intentions. In all of these activities improvisation plays a central part, and thus it might be said that whenever musicians cross boundaries they engage to some degree or the other in the act of improvising, and thereby becoming vulnerable and exposed, leaving behind the known musical world.

The many splendored thing called improvisation is often the driving force behind those magical moments in which we discover layers of emotional meaning in music that were previously hidden from our ears. Take for instance the miraculous improvisations of the French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard who often links together the pieces on his concert programs via beautifully woven improvisations. Here, the listeners are invited to re-enter the musical imagination of the composer whose piece they just heard by way of an improvisational afterthought.

Or take for instance the cool, detached, yet strangely powerful improvisations of Jacques Loussier that affected how an entire generation of Bach connoisseurs was listening to Jazz music. At the same time Loussier’s improvisations changed the way that people would listen to Bach’s music. I for one can’t get his weirdly retained introduction to the E-flat minor Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier out of my head. Whenever listening to someonelse’s interpretation I will inevitably compare it to Loussier’s rendition.

It is this exciting act of relating the presence of the musical performance to a commonly shared repository of musical ideas, concepts, and tropes that makes improvisation so central to our private and intimate experience of music. By moving music across the boundaries of convention and tradition improvisation constantly reinvents and questions our personal musical universe.

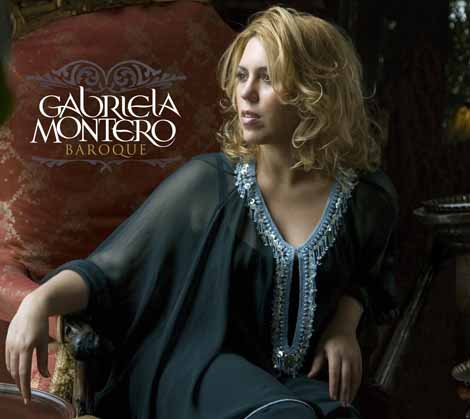

In recent years there has been a resurgence of albums that were in one way or the other indebted to improvisation. Once such album is Gabriela Montero’s “Baroque” (EMI Records) released in 2007, produced (for a ton of money, I guess) in the famous Abbey Road Studios, and featuring fifteen loosely connected numbers. What ties these numbers together is for the most part the fact that their composers belong (unsurprisingly) to the Baroque era. It would be too much to expect that the selection of works on “Baroque” goes beyond the usual suspects. We find a few movements from Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons scattered all over the place, Johann Pachelbel’s unavoidable Canon, Tomaso Albinoni’s Adagio, and Georg Friedrich Händel’s Hallelujah Chorus.

As one fears already from the unimaginative programming, the music itself isn’t very convincing either. Throughout the album Montero’s improvisations aren’t much more than an (undoubtedly) impressive display of all the different ways one can apply Kitsch to completely worn out “classics” of the baroque repertory. The best moments on “Baroque” are those numbers in which Montero mixes musical styles as for instance with the “Hallelujah” chorus that morphs into a Habanera-like rendition of the famous Handel signature tune, or with the latino-style Scarlatti sonata that transplants the Spanish music of the Neapolitan composer into a South American dance-hall atmosphere. That these moments owe much of their musical impact not to the power of improvisation but rather to the method of crossing the boundaries of genres is apparently no coincidence. Cross-over artists have been a major source of income for the ailing classical music industry and this album by Montero will be no exception in this respect.

While listening to the album, reading the liner notes, and browsing Montero’s website one cannot help the feeling that the artist would have probably been better off not to team up with EMI and Big Life Management for this project. Judging from Ms. Montero’s earlier projects – especially the Rachmaninov and Prokofiev album with Gautier Capucon – she is a capable musician. Even some of her earlier improvisations are worth their while. Maybe a bit more real improvisation, the one that goes beyond the boundaries of the average musical imagination and less of the kind that crosses the boundaries into a world of boredom and triviality would have helped this present undertaking as well. Whether Gabriela Montero in crossing all those boundaries has to be considered a “revolutionary or fool” in Gulda’s words is for the listener to decide.

Discussion

No comments for “Why improvise? A Review of Gabriela Montero’s New Album “Baroque””