By Zoë Lang

Recently, I have been thinking quite a bit about Gershwin’s 1935 opera Porgy and Bess, mostly due to the fact that we are talking about it in one of my classes. I’ve found this work to be fascinating from several perspectives, particularly in Gershwin’s incredible fluency between different musical styles. His ability to move seamlessly from one idiom to the next is unmatched and makes him stand out from many of his contemporaries who sought to integrate new sounds in their music but were ultimately unsuccessful. Porgy and Bess shifts from what sounds like a Hollywood soundtrack (‘Bess, you is my woman’) to complex ensembles (the funeral scene that opens Act I, scene ii) to standards that continue to be performed even today (one rendition of ‘Summertime’).

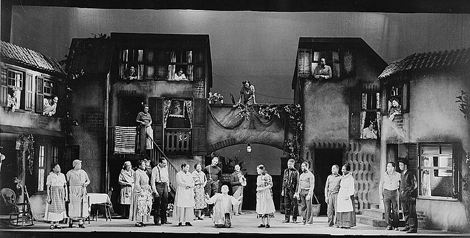

Yet despite the many riches that the score has to offer, I found myself strangely frustrated with the ending, specifically the actions of Bess. During the opera, Bess becomes involved with three different men: the dangerous and powerful Crown, who murders a man over a game of craps; the crippled beggar Porgy, who shows his dedication and steadfastness throughout the opera, including his willingness to kill Crown and neutralize the threat he poses on the community of Catfish Row; and Sportin’ Life, a drug-dealing smooth talker who spends most of the opera trying to win Bess over by offering her drugs and the promise of urban life in New York. We see Bess go from a drug-addled woman of loose virtue (when she is with Crown) to a member of the community (when she is with Porgy); in the version that I watched (the Trevor Nunn production) she walks around for much of Acts III and IV with an orphaned baby, physical proof that she is fully integrated and a responsible citizen of Catfish Row. In the end, though, Bess succumbs to her darker nature. With Porgy in jail for a contempt of court violation, Sportin’ Life makes his move by offering her drugs. While she initially tries to resist, we learn upon Porgy’s return that Sportin’ Life and Bess have left for New York (you can hear Sammy Davis Jr. entreating Bess to join him on the boat to New York starting at 5:35. Sammy Davis Jr. played Sportin’ Life in the 1959 film).

I will admit that I was disappointed with Bess: I had hoped that her character had moved beyond her sordid past and become a permanent fixture in the community. However, the more I thought about the fact that I found Bess’s actions to be disappointing, the more I realized that I was accustomed to operatic women seeming to have little to no control over their fates; so many of these stories make these deaths seem inevitable: Carmen, Tosca, Violetta, Gilda, Mimi, Desdemona, and others. Yet this train of thought also opened my eyes to the fact that women with no agency occupy my operatic world. When one of them makes a decision with which I disagree, I am disappointed in her and wish that she had behaved better. Whereas if a soprano is violently assaulted and killed on stage, I view this as completely normal.

Opera relies on an almost super-human suspension of disbelief, drastic temporal shifts, improbable plots, and violent acts. At the same time, there are few genres that have proven as malleable and durable. Perhaps it is in these incongruities that the fascination lies: knowing the end, we can no longer believe in Bess from the beginning, even though her failings make her one of the most human characters to appear on the operatic stage.

Discussion

No comments for “Porgy, Bess, and Agency”