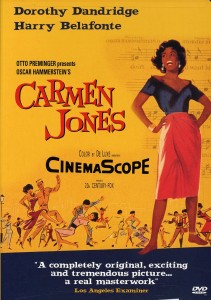

Recently, I traveled on a 14-hour long-haul flight from MEL to LAX. As a result, I was able to watch numerous films to help pass the time–if you are curious, the grand total that I watched during the 14-hour flight was seven. One of them, curiously, was Otto Preminger’s Carmen Jones, the 1954 re-imagining of Bizet’s Carmen. I have no idea how this film wound up in the Virgin Australia rotation, but I watched it and found it to be an inventive reinterpretation of the opera.

Recently, I traveled on a 14-hour long-haul flight from MEL to LAX. As a result, I was able to watch numerous films to help pass the time–if you are curious, the grand total that I watched during the 14-hour flight was seven. One of them, curiously, was Otto Preminger’s Carmen Jones, the 1954 re-imagining of Bizet’s Carmen. I have no idea how this film wound up in the Virgin Australia rotation, but I watched it and found it to be an inventive reinterpretation of the opera.

Carmen Jones, with a book by Oscar Hammerstein II, was initially presented on Broadway in 1942 with an all-black cast. It is not hard to see parallels between this production and Porgy and Bess (1935), which was also intended to showcase African-American performers on Broadway. As Alex Ross discusses in the chapter ‘Invisible Men’ from his book The Rest is Noise, there were a number of shows written for the many talented and classically-trained black performers who were often limited in their performing opportunities. Carmen Jones, which essentially preserves the original music, requires the same level of skill as the opera itself. In the movie, the part of Carmen was sung by Marilyn Horne in her first major classical role; Dorothy Danbridge acted the part, which was viewed as too challenging for her to sing.

While the melodies remain intact, there were considerable changes to the lyrics and to the settings, making the opera a modern adaptation of a classic. Take, for instance, Pearl Bailey’s ‘Beat Out That Rhythm,’ a new version of ‘Les tringles des sistres tintaient.’

From this clip, it is clear that Carmen Jones poses some problems in terms of race depiction: there is an exoticism that can be found throughout the film, much like the exoticism that drives the opera itself. If anything, the exotic qualities are made even more apparent since the movie takes place exclusively in a black world: we see effectively no white characters in the entire production, creating an artificial sense of segregation. Yet at the same time, the characters in Carmen Jones are less of a caricature than their operatic precursors. In fact, by making these characters more human, the traditional interpretation of this work gets turned on its head.

Borrowing from Catherine Clément’s Opera, or the Undoing of Women, Carmen’s fundamental flaw is herself. She is unwilling to compromise for anyone, repeatedly subverting attempts by the males in the opera to control her and disregarding conventional mores, such as the impending wedding of Don José and Micaëla. As a result, Carmen must die: violently and in full sight of the audience. The implication of this interpretation is that if she had chosen to follow the rules of society, she never would have suffered the fate that she did at the hands of Don José. It is her character’s traits that effectively kill her. To put it another way, she has brought this upon herself.

Carmen Jones shares some of the original Carmen’s traits. She has little interest in conventional society, proclaiming that she does not waste time worrying about the future. Her greatest fear is being trapped in a cage, a metaphor that can be applied literally (she refuses to go to jail) or figuratively (she is aloof in relationships). In the film, which never states the year in which it is set, she works in a parachute factory which is next to an army base, where Joe (Don José) is stationed. Before he gives in to Carmen’s charms, he is slated to go to flight school and become a pilot, a position of high esteem. However, he is forced to leave his position after he kills one of his commanding officers because he was flirting with Carmen. Joe murders the officer by beating him to death with his fists, seemingly unaware of his power. He and Carmen flee to Chicago to avoid his capture. While he is trapped in the apartment, he continues to make threats to her: if she leaves, he will find her. Of course, in the end he does, and strangles her on camera.

Joe’s character is contrasted with Husky Miller, the stand-in for Escamillo. His introductory song, to the tune of ‘Toreador,’ is ‘Stand Up and Fight’ (seen in the preview of the movie).

Undoubtedly, a toreador would be out of place in rural America, so his role is transformed into a boxer. During a stopover in Carmen’s town, he was besotted with her and demanded that his manager bring her to Chicago, where he is about to fight. Carmen is initially reluctant, then takes the money to transport her and Joe after he has murdered the officer. Carmen does succumb to Husky eventually. However, we see that his personality is different than that of Joe’s. Husky tries to seduce Carmen, but when he is rebuffed, he does not threaten her. Instead, he is patient. When Joe seeks to fight Husky, Husky is the one who refuses since he knows that he has the power to kill Joe with his fists. This contrasts heavily with Joe, who was oblivious to his strength.

In Carmen Jones, then, the problem is not so much Carmen, who is content to live her life. The problem is Joe. He is unable to control his impulses, killing a man–then later Carmen–with his bare hands. Certainly, it is easy to say that he was driven to this behavior, but that does not work in this interpretation, particularly after we see that Husky is able to control his emotions even when under the influence of the bewitching Carmen. It is not her fault, then, that she died. It is Joe’s fault that he is unable to stay in control when he should.

This lack of control is treacherous, not only for Carmen, but also because of Joe’s role in the military. He was supposed to become one of the elite members of the air force, a position that is repeatedly referred to by the various characters as one of great prestige. But his inability to control his emotions makes one wonder if he was really suited for this position. This work debuted during wartime and in 1954, audiences would have been cognizant of the importance of discipline for members of the military: World War II was not that far in the past and the Korean War had just ended (1953). What if a Joe were in the military? We start to see that his behavior is not merely damaging to those who are killed in the film, but potentially threatening to other officers and to the integrity of his unit.

Carmen Jones takes a classic opera and reinterprets it for a modern audience. In doing so, though, it also provides an alternative understanding of the characters by rendering them more human. While the film is worth seeing in and of itself, for opera buffs, it is particularly recommended since it offers a new take on a perennial favorite.

Interesting fact: the role of Joe was played by Harry Belafonte, although his voice was also dubbed in the songs because they were considered too difficult for him. Belafonte would later refuse to play the role of Porgy in Preminger’s Porgy and Bess because he felt it was a demeaning portrayal of a black man. Of course, Belafonte is far more famous for his songs, two of which were integral to another film that I watched on my trip, Tim Burton’s 1989 Beetlejuice.

Discussion

No comments for “Whose undoing? Carmen Jones and the multiciplicity of interpretation”