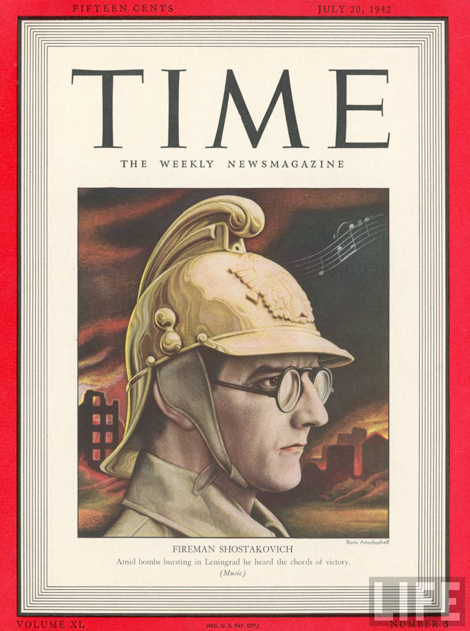

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri ShostakovichThis photo graced the cover of the July 20, 1942 issue of Time Magazine. The story discussed the upcoming radio broadcast by the NBC Orchestra of Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony (‘Leningrad’), a piece that had been brought via 100 feet of microfilm from Kuibyshev to Teheran, then to Cairo, and finally to New York. Time considered this work to be the most highly anticipated American debut since the 1903 Manhatten premiere of Parsifal, a piece that was apparently so lofty as to be devoid of political ideology or national origins.

The description of the ‘Leningrad’ identifies it as a symphony that does not quite succeed as an example of its genre:

‘Written for a mammoth orchestra, Shostakovich’s Seventh, though it is no blatant battle piece, is a musical interpretation of Russia at war. In the strict sense, it is less a symphony than a symphonic suite. Like a great wounded snake, dragging its slow length, it uncoils for 80 minutes from the orchestra. There is little development of its bold, bald, foursquare themes. There is no effort to reduce the symphony’s loose, sometimes skeletal structures to the epic compression and economy of the classical symphony.’ (53)

This is not to say that the symphony did not accurately capture its Zeitgeist:

‘Yet this very musical amophousness is expressive of the amorphous mass of Russia at war. Its themes are exultations, agonies. Death and suffering haunt it. But amid bombs bursting in Leningrad [ed. note: not ‘in air!’] Shostakovich had also heard the chords of victory. In the symphony’s last movement the triumphant brasses prophesy what Shostakovich describes as the “victory of light over darkness, of humanity over barbarism.”‘ (53)

There are more detailed ‘program notes’ that follow, such as this description of the first movement:

‘The deceptively simple opening melody, suggestive of peace, work, hope, is interrupted by the theme of war, ‘senseless, implacable and brutal.’ For this martial theme Shostakovich resorts to a musical trick: the violins, tapping the backs of their bows, introduce a tune that might have come from a puppet show. This tiny drumming, at first almost inaudible, mounts and swells, is repeated twelve times in a continuous twelve-minute crescendo. The theme is not developed but simply grows in volume like Ravel’s Boléro; it is succeeded by a slow melodic passage that suggests a chant for the war’s dead.’ (54)

I have a lovely mental image of households across America tuning in to hear Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, Time Magazines in hand, following along with the broadcast. Does anyone know if they ever tried this with Webern?

Biographical information about Shostakovich is provided, including a remarkably jaunty retelling of the Lady Macbeth scandal:

‘At the height of the Purge, when Russian nerves were badly frayed and people were plopping into prison like turtles into a pond[!], Stalin decided to hear Lady Macbeth. He did not like it, walked out before it was over. Murder from boredom struck him as a bourgeois idea. Besides, Stalin’s musical taste runs to simple, more tuneful things, zigzags between Beethoven’s Eroica and Verdi’s Rigoletto[!]. Also, he had a seat directly above the brasses.’ (54)

There is also a description of Shostakovich, the man:

‘At parties or among musicians, he unbends, jokes, outdrinks his companions. He likes automobiles, fast driving, U.S. magazines, reads the U.S. authors who most appeal to Russia — Mark Twain, Jack London, Theodore Dreiser, Upton Sinclair Strictly a city man, he dislikes dachas (Russia’s summer bungalows) and komaryi (Russia’s multitudinous mosquitoes).’ (55)

The article ends with an attempt to contextualize the Seventh Symphony and Shostakovich’s oeuvre: ‘Is Composer Shostakovich the last peak in the European musical range whose summit was Beethoven, or is he the beginning of a new sierra?’ (55)

Undoubtedly, you are curious to know why Shostakovich is wearing a fire helmet on his front cover. When he was still in Leningrad during the Second World War (prior to his evacuation), he served in the citizens’ reserve fire brigade.

[…] es el primero de ellos quien logra estrenar la obra el 19 de julio de 1942 en Nueva York. La revista Time saca en portada a Shostakovich vestido de bombero y el compositor pasa a ser un símbolo de la causa aliada, un modelo de […]